I know a good leader when I see one, and have photographed hundreds during my 50-plus years of documenting history. Some of them are definitely better than others.

President Gerald R. Ford was not only a good leader, but in my opinion one of the best. There are many qualities that inhabit a good leader, and President Ford had most of them.

It takes guts to be a good leader. On August 19, 1974, ten days after becoming president of the United States, Gerald R. Ford announced to the National Convention of Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW) in Chicago that he would be granting conditional amnesty to those who were being sought as draft evaders or military deserters from the Vietnam War. He proposed a program that would allow them to work their way back. “I did this for the simple reason that for American fighting men, the long and divisive war in Vietnam has been over for more than a year, and I was determined then as now to do everything in my power to bind up the nation’s wounds.” This was not going to be a popular decision with the VFW group, and on the way over to the convention President Ford told me with a laugh, “At least I don’t have to worry about being interrupted by applause.” Rather than going in front of an audience that he knew would cheer his decision, he went into the lion’s den. To him it was the right thing to do, and even though the VFW attendees didn’t like the plan, they appreciated their fellow veteran laying it out for them first.

A good leader does the right and courageous thing despite the consequences. When Gerald R. Ford took office after the resignation of President Nixon, his approval rating stood at 77%. Much of that goodwill certainly reflected America’s relief after Nixon’s exit, and hearing from Ford during his speech upon taking the oath of office as president that, “our long national nightmare is over.” That warm feeling didn’t last long. On September 8, 1974, just 30 days after taking office, President Ford granted Richard Nixon a pardon. It was a wildly unpopular act. By January of the following year, his approval rating had plummeted 34 points to 37%. The pardon likely cost him the 1976 election, even though he fought back to an almost dead heat against Jimmy Carter two years later. In 2001, the 87-year-old former president would receive the John F. Kennedy Library’s “Profile in Courage” award. The award was jointly presented to him by Senator Edward Kennedy, who had publicly condemned him for the pardon, and JFK’s daughter, Caroline Kennedy. Ms. Kennedy said President Ford had proved that “politics can be a noble profession,” and cited his “controversial decision of conscience” in issuing the pardon. Senator Kennedy noted, “I was one of those who spoke out against his action then. But time has a way of clarifying past events, and now we see that President Ford was right. His courage and dedication to our country made it possible for us to begin the process of healing and putting the tragedy of Watergate behind us.” President Ford told me afterwards that receiving the “Profile in Courage” award was one of the best moments of his life.

A good leader is democratic. President Ford was a consensus builder. He had to be, as he was in the minority party for all but three years of his time in public office, a career that began in 1948. His relationships with Democrats were excellent, and one of his best was with Massachusetts Congressman Tip O’Neill, the crusty Majority Leader of the House during Ford’s time as vice president and president. The two of them would fight like cats and dogs during the week over their political agendas, but would play golf together on the weekends. President Ford’s philosophy was, “You can disagree without being disagreeable.” That attitude went a long way toward getting the things he wanted to accomplish done.

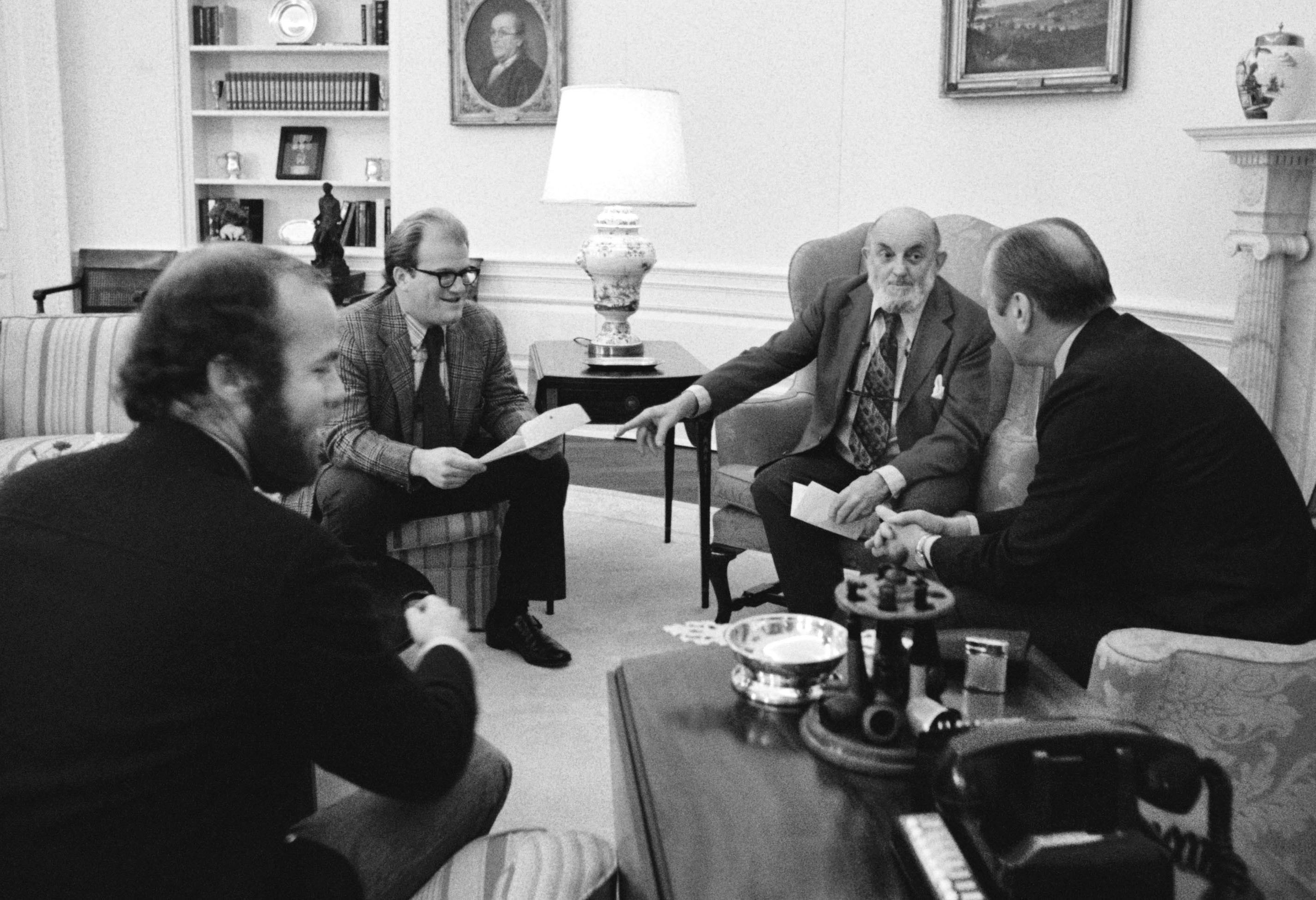

A good leader is visionary. This is particularly true when you talk about meeting with the great photographer and environmentalist, Ansel Adams! I arranged a conference with President Ford and Ansel to discuss Ansel’s favorite subject, the national parks. The meeting was off to a good start as President Ford proudly showed Ansel his framed photo of “Clearing Winter Storm” that Ansel had sent him ahead of the meeting hanging prominently over the fireplace in his private office. This might have been the first time a photograph had been displayed as art in the White House.

Once seated, Ansel got right down to his subject: he was distressed about what he felt was the mismanagement of the park system. The president told Ansel, "If anyone has a feeling for the national parks, I do." Ford said that in the summer of 1936 he was a ranger at Yellowstone National Park where, among other duties, he monitored and fed the bear population. (That practice has long since been discontinued, but it might well have prepared Ford for a career in politics.) President Ford told Ansel that the experience was, “one of the greatest summers of my life.” To this day he is the only U.S. president who ever served as a park ranger.

Ansel, like President Ford, was a good-natured guy who possessed inner steel and exuded a quiet strength. During the meeting with President Ford, despite the bluntness of his words, Ansel spoke softly and the president responded in kind, often leaning in to hear each other more clearly. One of the things that attracted Ansel to the president was that, like himself, he was a modest and self-effacing man. But Ansel was on a laser-guided mission and made his points about the preservation and expansion of the parks his number one priority. Ansel had an attentive audience and painted a magnificent picture of what the president could do to make the parks even better.

Not long after their encounter, President Ford wrote to Ansel agreeing with him that the National Park Service policies "needed a fresh look," and reporting that he had commissioned a task force to redefine its priorities. But a task force wasn't enough for Ansel and in his typically politic but feisty style, he wrote the president, "I believe the president, more than anyone else, must be exposed to frank and candid views, even if they differ in substance, as mine will in this letter. But I respond in a spirit of constructive candor because I have a great respect for your openness and remarkably direct approach." He said that the working group gave him little comfort, "as the task force is totally internal and led by a tired, superannuated bureaucrat ... What kind of new and truly imaginative broad-scale thinking can we expect from a group of that caliber and composition?" Nobody ever accused Ansel of mincing words! He went on to say, "Only you can set the priorities. Only you can stimulate new approaches and new levels of energy. I deeply believe that the American people would respond, in the Bicentennial Year, to bold leadership from you on a program of National Parks for the Future.”

Many presidents would have told Ansel to go to hell after that kind of pushback, but not President Ford. Ansel’s letter and proposals struck a deep chord within the president, and he stepped up in a big way. The following year President Ford stunned the environmental world and both political parties by announcing that he would be submitting to Congress the "Bicentennial Land Heritage Act," a multi-billion-dollar commitment to the national park system. Standing in front of Old Faithful, President Ford began by saying, “As I thought about the changes that have taken place in this great country . . . I also thought about those things that must never change . . . We must be equally committed to conserve and to cherish our incomparable natural heritage-- our wildlife, our air, our waters, and our land . . . I decided upon a 10-year national commitment to double America's heritage of national parks.” (This was right out of the Ansel Adams playbook). “This national commitment means we may have to tighten our belts elsewhere a bit, but it is the soundest investment in the future of America that I can envision. We must act now to prevent the loss of treasures that can never be replaced for ourselves, our children, and for future generations of Americans . . . I want to be as faithful to my grandchildren's generation as Old Faithful has been to ours.” Making his point in spectacular fashion, the faithful geyser erupted during his remarks, spewing water and steam hundreds of feet into the air. It was the ultimate photo op, not to mention great planning by the president’s advance staff! Shockingly, the 94th Democrat-controlled Congress killed the president’s bill, most likely believing it would have been a political advantage for President Ford in the upcoming presidential election. He was furious and to underscore his displeasure, and in one of his final acts as president, he re-submitted the proposal to Congress on Jan. 20, 1977, just hours before he left office. Had the legislation been passed, President Gerald R. Ford could well have been considered the greatest environmental president since Teddy Roosevelt, and that would have been thanks in great part to Ansel Adams.

Part two of this “Leadership Through the Lens” series will be released next month…Stay tuned!

David Hume Kennerly has been a photographer on the front lines of history for more than fifty years. At 25 he was one of the youngest winners of the Pulitzer Prize in Journalism for Feature Photography, an award that included images of the Vietnam War. Two years later Kennerly was appointed President Gerald R. Ford's personal White House photographer. American Photo Magazine named him “One of the 100 Most Important People in Photography.” He is currently a contributor to CNN.

Kennerly is the author of seven books. The most recent, David Hume Kennerly On the iPhone, was released in the fall of 2014. Previous books include Shooter, Photo Op, Seinoff: The Final Days of Seinfeld, Photo du Jour, and Extraordinary Circumstances: The Presidency of Gerald R. Ford. He also produced, “Barack Obama: The Official Inaugural Book,” and was one of its principal photographers.

David Hume Kennerly was a featured speaker at the Rumsfeld Foundation’s 2018 Graduate Fellowship Spring Retreat. He also provided the entire collection of photographs used throughout Donald Rumsfeld's latest book, "When The Center Held." Rumsfeld’s profits from the book are donated to the Foundation in support of its Graduate Fellowship Program.